Lecture 1: Renal anatomy, functions, and filtration barriers

Slides from University about Renal Anatomy, Functions & Filtration Barriers. The Pdf explores the anatomy of the kidney, its filtration functions, and barriers, detailing excretion, reabsorption, and biosynthesis processes. The Presentation, suitable for University Biology students, describes key structures like the medulla, cortex, and nephrons, illustrating hormone production and renal gluconeogenesis.

See more11 Pages

Unlock the full PDF for free

Sign up to get full access to the document and start transforming it with AI.

Preview

Renal Anatomy and Filtration Barriers

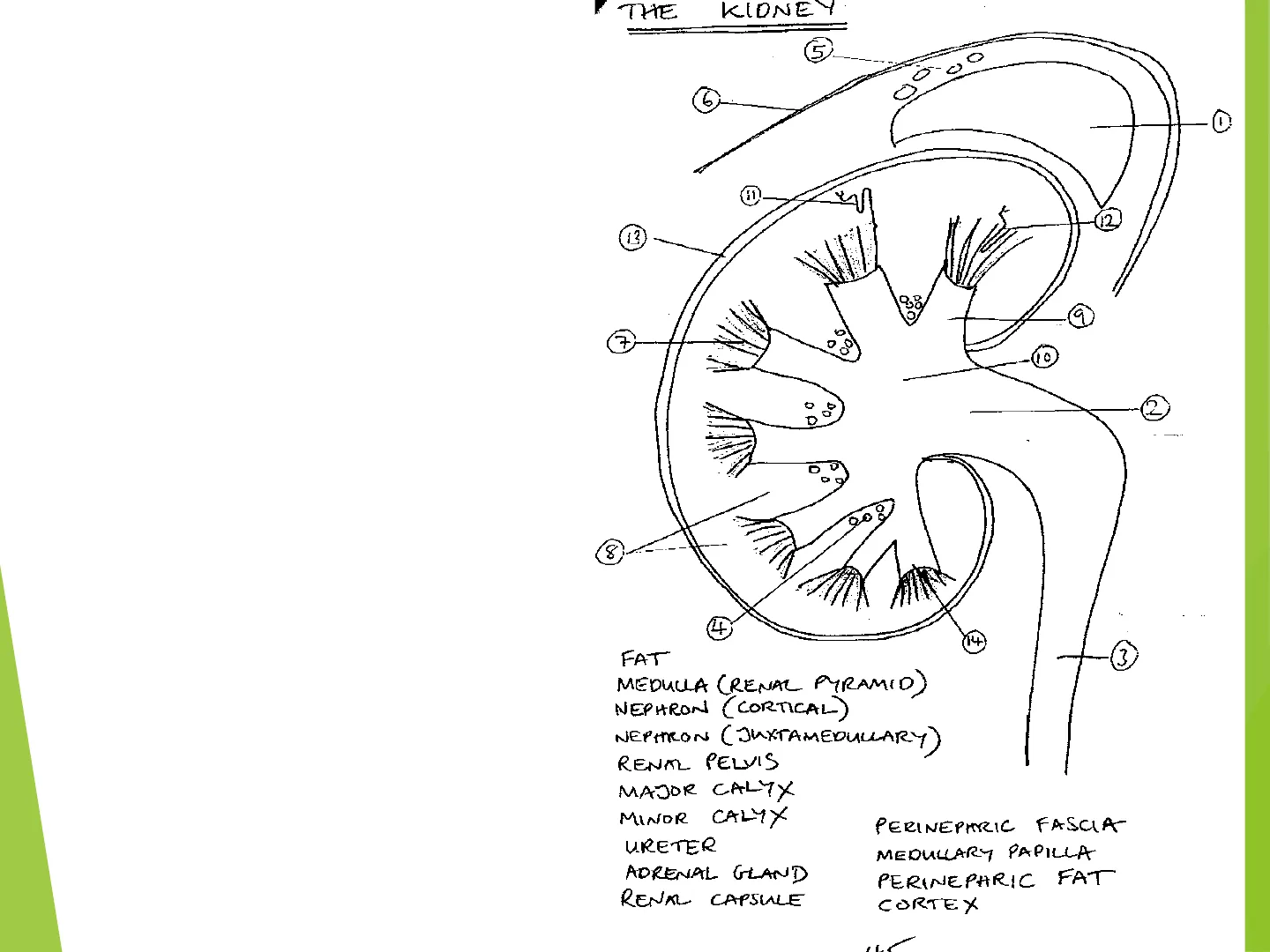

Here is the gross anatomy of the kidney, looking at a sagittal section. You can see the kidney parenchyma is made up of 2 major regions: I. The inner medulla (organised as medullary pyramids) II. And outer cortex, which provides the surrounding renal tissue but also forms cortical columns between medullary pyramids. The kidney is sheathed in a tough renal capsule, with extra protection and insulation being afforded by perinephric fat.

Nephrons, the functional filtration (renal corpuscle) and filtrate modification (renal tubule) units, of which there are about a million per kidney, are found either largely in the cortex (cortical nephrons, the majority) or with part of their structure (an especially long Loop of Henle) deep in the medulla (juxtaglomerular nephrons, the minority). The medullary pyramids comprise asse mbled renal tubules and collecting ducts that drain the nephrons. Urine is funnelled by minor and then major calyxes into the renal pelvis, which is itself then drained by the ureter connected to the bladder. The bladder of course communicates with the external worldTHE KIDNEY

1=adrenal gland 2=renal pelvis 3=ureter 4,5=fat 6=fascia 7=medullary pyramid 8=cortex 9=minor calyx 10=major calyx 11=nephron (cortical) 12=nephron (juxtamedullary) 13=capsule 14=medullary papilla 30.00 6, 0 12 13 9 7 0 DO 2 0 D 0 000 8 : 4 14 3 FAT MEDULLA (RENAL PYRAMID) NEPHRON ( CORTICAL) NEPHRON ( JUXTAMEDULLARY ) RENAL PELVIS MAJOR CALYX MINOR CALYX URETER ADRENAL GLAND RENAL CAPSULE PERINEPARIC FASCIA MEDULLARY PAPILLA PERINEPARIC FAT CORTEX

The Nephron Structure

Here is the anatomical breakdown of a renal nephron, composed of epithelial cells. I. Starting with the proximal end, we have Bowman's capsule, which together with its capillary blood supply the glomerulus, helps form the renal corpuscle. II. A proximal convoluted tubule follows, giving way to the Loop of Henle (comprising a descending limb, actual loop and ascending limb, which has a relatively thick segment in juxtaglomerular nephrons, i.e. the thick ascending limb of the Loop of Henle). The Loop precedes the distal convoluted tubule, which then drains into a collecting duct.

Functional Unit of the Kidney

Composed of : Renal corpuscle ( = Bowman's capsule + glomerulus) = site of ultrafiltration Renal tubule Proximal tubule (PT) Loop of Henle (LH) Distal tubule (DT) =sites of tubular modification Drained by collecting duct

Filtration Barriers

Fenestrated endothelium Permeable to water, solutes, most proteins but not blood cells Basement membrane Porous matrix of collagen, laminin, agrin etc Charge-selective filter, plasma proteins cannot cross Podocytes (epithelium) Size-selective filter, bars passage of protein and macromolecules that have crossed basement membrane Molecules <7000 Da are freely filtered e.g. glucose, amino acids, drugs e.g. loop + thiazide diuretics (NB: protein-bound drugs cannot be filtered)

Returning to the head of the nephron and the site of glomerular ultrafiltration at the renal corpuscle, we have the 3 filtration barriers that enable filtration of the blood. The newly formed renal filtrate that progresses along the nephron on its way to becoming urine (we need to remember here that urine is modified filtrate, i.e. a product of both glomerular ultrafiltration and tubular modification (represented by tubular secretion and reabsorption)). Starting with the blood side, we have fenestrated (or essentially perforated) endothelium that lines the glomerular capillary blood vessels and is very highly permeable to the passage of water/plasma (but not of course the passage of blood cells or platelets). This make fenestrated endothelium a size-selective filter. ❖ The next barrier encountered is the basement membrane, a porous, negatively charged matrix of connective tissue proteins including type IV collagen. This represents a charge-selective barrier that deters plasma proteins from crossing into the filtrate. ❖ Finally, we have a barrier constituted by epithelial cells arranged as podocytes with interdigitating pedicels (think of overlapping teeth on a couple of hair combs!). This represents another size-selective filter that bars the passage of any plasma proteins that have managed to make it that far. One of the main results of these filtration barriers is that anything 7000 Daltons or greater in molecular size, will likely not enter the urine and will remain in the blood. However, plenty of useful substances that we'd rather remain in the blood will be freely filtered owing to their small size, such as glucose and amino acids - and drugs too, if they're not protein-bound. Happily, for glucose and amino acids, these are normally reabsorbed by the proximal tubule back into the blood.

Renal Disorders Involving Filtration Barrier Breakdown

Nephrotic Syndrome

- Podocyte barrier dysfunction

- Proteinuria - loss in urine of immunoglobulins (lgs), albumin, anti-thrombin, lipoproteins

- Hypoalbuminaemia, leading to severe oedaema

- Increased risk of infection, thromboembolism, hypercholesterolaemia

Alport's Syndrome (Hereditary Nephritis)

- Basement membrane dysfunction

- Loss of blood cells in urine (hematuria) + proteinuria

- Inflammation of glomerulus (glomerulonephritis)

- Extra-renal symptoms incl. deafness + ocular changes

Of course, things can go wrong with barrier function and here we have some major disorders involving renal filtration barrier breakdown - nephrotic syndrome and Alport's syndrome. Nephrotic Syndrome, this is a podocyte barrier dysfunction that allows plasma proteins (in the form of e.g. albumin, immunoglobulins, clotting factors and lipoproteins) to be lost in the urine. ❑ Result: ❑ Starting with The loss of albumin alters the osmolality of the blood, leading to a net movement of water into tissue and a state of severe oedema, which may be generalised to the whole body (this is anasarca). ❑ Other consequences of this protein loss include an increased risk of infection (in view of the loss of circulating antibodies), an increased risk of blood clotting and high blood total cholesterol (owing to an imbalance in clotting factors and an a disproportionate loss of HDL, respectively). In Alport's syndrome, a rare hereditary nephritic disorder, type IV collagen, a major component of the glomerular basement membrane among other sites, is defective. Result: This is associated with not only renal problems, such as the appearance of blood and protein in the urine and inflammation, but also extra-renal problems including pathology affecting the inner ear and eyes.

Renal Functions: Excretion

Now it's time to consider what our kidneys do for us! Excretion is probably the first job that comes to mind, especially in connection with getting rid of nitrogenous waste products like urea, creatinine (a breakdown product of muscle creatine) and uric acid. Electrolytes such as sodium, potassium, chloride and bicarbonate anion as well as drugs (if they're freely filtered at the glomerulus) and naturally water too, are also standard excretory products in urine, which commonly amounts to around 1.8L volume per day. Urinary volume is naturally variable though; and depending on the amount of water the body has to waste (state of hydration) and the filtered solute load that has to be excreted, urine strength or osmolality can typically vary in humans between 50 to 1400 mOsmol/kg water. But of course, the kidneys are about a lot more than simply excretion.

Excretion Products

- Nitrogenous waste products e.g. urea, creatinine, uric acid

- Water

- Electrolytes

- Drugs

Renal Functions: Reabsorption

v With the entire blood circulation typically being filtered in around 24 minutes in adults and the attendant prospect of imminent dehydration not to mention desiccation, it's clear that the reabsorption of most of the water (typically 99%) filtered from the blood, is one of several urgent renal priorities! In fact, some 80% of filtered water reabsorption from the renal tubule is guaranteed or obligate; with the remaining 20% being optional or facultative from the collecting duct (and this facultative water reabsorption is under the influence of the posterior pituitary hormone, antidiuretic hormone (ADH)). Some other primary renal concerns include reclaiming all the glucose and amino acids that have been filtered and that can't afford to be wasted. In contrast, the reabsorption of filtered electrolytes is more variable or facultative. The excretion of urea happens to be variable by virtue of the fact that urea crosses cellular membranes easily and can therefore diffuse from the urine back into renal tissue and subsequently back into the blood.

Reabsorption Summary

- Water (99% normally, but variable)

- Glucose (100%)

- Amino acids (100%)

- Electrolytes (variable)

- Urea (variable)

Renal Functions: Biosynthesis

Another dimension to renal function concerns a biosynthetic role: vis-à-vis the production hormones e.g. calcitriol, erythropoietin and the enzyme renin (which initiates the renin angiotensin aldosterone system). Another important kidney product is the renal natriuretic (i.e. it causes sodium excretion in the urine) peptide, urodilatin. What may be particularly surprising is that the kidneys additionally have the biochemical potential to generate de novo glucose, in response to starvation - a biological feat more commonly associated with the liver!

Biosynthesis Products

- Calcitriol (active form of vitamin D)

- Erythropoietin (EPO)

- Renin

- Urodilatin

- Glucose (gluconeogenesis) in starvation

Renal Functions: Regulation

V This slides considers the "bigger picture" of renal function, in terms of what individual renal functions support on a larger, often homeostatic scale. Such functions include the: regulation of blood volume and related blood pressure; acid-base balance/blood pH; electrolyte balance; calcium metabolism; red blood cell production; regulation of the activity of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS); and not forgetting the basics of simple diuresis, natriuresis and kaliuresis (the renal excretion of potassium)!

Regulation by Kidneys

- Blood volume + therefore blood pressure

- Acid-base balance + blood pH

- Electrolyte balance

- Calcium metabolism (via calcitriol)

- Erythrocyte formation (via EPO)

- Renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) (via renin)

- Diuresis (water loss) + natriuresis (sodium loss) (via urodilatin)

- NB: kaliuresis = potassium loss